I am very grateful to Cardano for supporting me in taking a sabbatical after 17 years with the company. I turned 50 this year, my eldest son has just finished school and my new role in sustainability last year all converged to make it feel like an opportune moment to take some time out to seek inspiration and direction for this next stage of my career.

The sabbatical was always going to involve travel which we love doing as a family. But I wanted to combine that with an intentional connection to sustainability and to conservation at a grass-roots level. That also lead to the decision to split the sabbatical into two parts, 5 weeks over August this year and 9 weeks next year, to allow us to travel to different parts of the world. For this first August trip we focused on Africa, particularly Botswana and Tanzania and we were not disappointed.

We got very lucky in finding a conservation organization the PAMS foundation that work together with a local tour operator Dorobo safaris who were able to organize both safari experiences as well as local conservation experiences in Tanzania. The safaris in both Botswana’s Okavango delta and Tanzania’s Tarangire national park and the Ngorongoro crater were all spectacular and I could not recommend all these locations more highly for wildlife viewing, but the true highlights of our trip were the conservation projects.

We visited three different projects, in each case staying with locals in temporary tented camps, which I will tell you a bit more about:

1. Elephant/human co-existence in Kitete

Elephant/human coexistence project in Kitete on the highlands of the rift valley. The rift valley is an escarpment along a geological fault that runs for thousands of kilometers, separating a forested mountainous upper area in the east, from the savannah of the valley floor to the west. There is only one point along this escarpment where, for thousands of years, elephants have trampled a path from the highlands down to the valley floor. Two villages about 4 kilometers apart straddle the upper entrance to this elephant corridor and as a result local villagers and farmers come into frequent contact and conflict with the elephants. The project works on providing safe transport between the two villages and on putting up “chili fences” – cloths soaked in chili oil strung-up every 5 meters or so – around the perimeters of farms during the growing season. This keeps the elephants away from trampling the crops without locals needing to become aggressive in protecting their crops. Elephants remember when an location is dangerous to them which makes them more aggressive so the secret is in finding these techniques that prevent the conflict from developing in the first place.

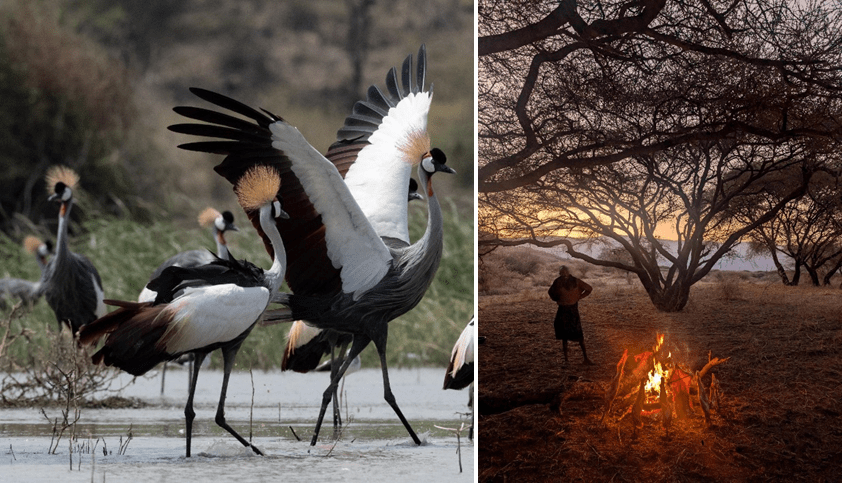

We hiked down along the elephant trail (fortunately not bumping into any elephant along the way!) and spent a second night camping in the wetlands of the Selala forest at the base of the escarpment in Maasai country. Here we had the privilege of meeting “Chuey” (“the leopard” in Swahili), a local Maasai man, enjoying a meal of roasted goat with him and canoeing on the wetlands with some spectacular birdlife including a flock of crowned cranes

2. Deforestation in the Nou forest

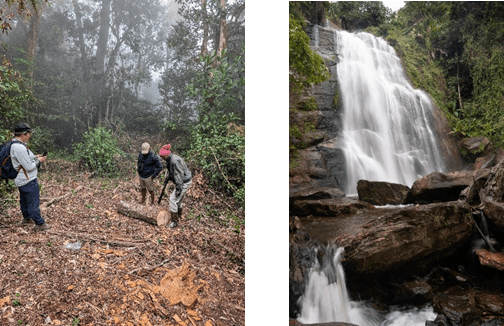

The second project was focused on deforestation in the Nou forest in the highlands. The Nou forest is an ancient rainforest located in mountains and home to the Iraqw people who are farmers. The farmers farm large fields in the valleys between mountain tops – it was garlic harvesting season when we visited.

The conservation project involves locals monitoring deforestation of the forests in the area, which is supported economically by bringing a few tourists in to experience the forest in temporary camps. Our guide, a local farmer called Carolee, lead us on a 4 hour hike through the jungle to a beautiful waterfall. Unfortunately we did come across the remains of a huge tree that had been felled recently, and began to understand the terrible impact of losing even a single large and ancient tree on the surrounding ecosystem.

We later got to spend some time with Carolee and his family at his farm, meeting his wife and bibi – his 80 year old mother and the matriarch of the family. We had been told about a rare species of chameleon unique to the Nou forest that we had been searching for, for days. Bibi disappeared into the trees on the edge of the farm and in 5 minutes returned with a magnificent specimen!

3. Societal conservation with the Hadza

The third project focused on the social conservation of a unique tribe of hunter-gathers called the Hadza. The Hadza have lived in the dry lowland area between the Serengeti and Ngorongoro for thousands of years. The landscape consists largely of baobab trees and acacia thorn trees. The Hadza are genetically unique and speak their own language that is completely unrelated to the surrounding Bantu tribes. They number only 1300 in total, a number that is unchanged since the 1950’s, living spread out in an area of around 40,000 hectares (200 square kilometers), an area that is considerably reduced since the 1950’s.

They keep no livestock, farm no crops and store no food overnight. They forage each day for tubers and hunt for anything from small birds and rodents through to large buck, buffalo and even on very rare occasions lion. The only exception is elephant which are too big for their poison to be effective, and a certain hornbill bird which they are superstitious about.

The woman collect tubers in the winter dry season and berries in summer. They will do this collectively – its a time to chat and commune while they dig tubers out of the ground with sticks and then roast them on a fire. They will start up a fire right where they are seated in the bush – the men start a fire in a matter of seconds by rapidly rotating a firestick on a piece of wood and kindling.

The tubers which are full of moisture grow underground and are similar to sweet potatoes. The act of digging them up triggers the vine to grow new tubers the next season as a store of food for the plant in case of drought which is not uncommon in the area.

The male children grown up with a bow and arrow in hand from the moment they can walk – we saw several 2 year-olds with bows in hand. By the time they are 7 they will be accomplished bowmen capable of surviving on their own if need be. They hunt opportunistically and are never with-out their bow and a clutch of arrows, in case they come across some animal on their travels. As a result most animals in their territory have learnt to be very reclusive and shy, though this does not prevent the Hadza catching them.

Because they rely on the land each day they need to move regularly so as not to exhaust the supply of tubers and wildlife in an area and hence they don’t have permanent villages. They build a few temporary grass huts in an area that they will stay for a few weeks, but they mostly sleep outside under the stars in this dry area.

One of the main objectives of the conservation project has been to secure their right to a portion of their former lands. They are surrounded on all sides by other tribes that have gradually encroached on their lands, either farmers like the Iraqw or pastoralists like the Maasai and Datoga who’s populations are growing and who need land for crops and grazing. The Hadza are far more equipped to deal with drought in this very dry area than these other tribes for whom drought typically means crop failure, the death of livestock and immense hardship.

Because of the increasing settlement around their territory by these other tribes less and less wildlife is able to make the transit from the Serengeti to their west through to Ngorongoro in the north east. This means there are far fewer of the larger animals for the Hadza to hunt these days, though they continue to hunt smaller deer, baboon and birds. Current conservation efforts are focused on opening a wild life corridor between these areas that will allow the animals on which they depend to continue to move through their territory.

The Hazabe (plural of Hadza) live together in loose coalitions in which everyone contributes each day. Their culture is very egalitarian, there is no village chief, elders are respected for their wisdom but no one person decides what they do. No hunter will brag about their role in a hunt (that would be very bad form) and anyone who asks (even those who come from groups elsewhere in the area) will get a share of either the tubers or catches of the day.

They prize their independence and ability to choose each day where and with whom they will live. Culturally they are extremely conflict avoidant, so if they are not getting on with someone they tend to just move out, including husbands and wives! But this conflict avoidance has been to their detriment as more assertive tribes surrounding them have encroached on their lands.

The do not seek to be disconnected from the outside world, but they do choose to continue to live in this manner, living from what nature will supply them each day. They wear regular clothes (mostly old football shirts donated to them because everyone else in Tanzania is crazy about English football) though they don’t have more than one pair. They trade wild honey that they collect for a few modern conveniences: tobacco and weed which they love smoking, parachute cord for their bows (these used to be strung with tendons from larger animals but parachute cord lasts much longer), metal knives and torches (torches for hunting at night) and nails – 4 inch metal nails are pounded into arrow heads when making their arrows.

We were immensely privileged to live in their territory for three nights. We spent most of our time with around 6 or 7 of their men and 2 of the woman who came to hang out at our camp and involved us in their daily activities, from visiting some other temporary villages to tuber foraging to making arrows to hunting. They were very welcoming and despite the language barrier (they could speak some Swahili with our guide) we quickly got to know and enjoy our time with different individuals. As westerners we went in fascinated by a “primitive tribe” and left feeling humbled by our own inadequacies, and awed by the skill, kindness, wisdom and joy of these people who have the ability to choose to live in such a unique way, in such inhospitable conditions.

I have many takeaways from our time in Africa, too many to expound on in this blog. But it did open my eyes to the reality that we have a tremendous amount to learn from other cultures and economic systems, very different from our own. We share a common humanity. Our dreams of creating a fairer and more sustainable society will work only when we truly connect with, respect and learn from other cultures.

For more photos from our adventures see the gallery here: CEWE-MyPhotos/African Adventure